For a computer, a three-dimensional space is a collection of triangles. In older 3D video games, this was noticeable and everything seemed a bit triangular. This was because, in order to accommodate older hardware, they had to reduce the number of triangles. Nowadays, there are more triangles, so there is more detail and things don’t seem triangular in modern video games – but deep inside, they still are.

Usually, computers treat media as pixels. An image is nothing but a collection of pixels. However, in 3D graphics, it’s more efficient to treat everything as triangles. With triangles, you can manipulate their angles and adjust shapes as someone moves within a 3D space.

Apart from what’s happening in front of the scene, some trigonometry is still needed behind the scenes for 3D worlds. Light and reflection are among the most important elements. For computers, light can also be thought of as a triangle. As light hits a surface and bounces, it creates a “V,” which is like a triangle without one side.

It makes sense that geometry plays a significant role in 3D graphics in computing. And as we all know, the most favored shape in geometry is the triangle.

The number of triangles in a 3D world is unbelievably high, and the better the graphics, the more millions of triangles there are. All those triangles are recalculated with every screen refresh and every movement of the player, all simultaneously. This is manageable because a computer’s job is to perform many calculations. However, the calculations are so numerous that we need a dedicated piece of hardware for them: the graphics card.

Even though humanity created dedicated hardware for these calculations, that alone wasn’t enough, and the calculations had to be optimized. We had to find ways to perform our calculations more intelligently and faster so we could handle more of them simultaneously, resulting in more triangles and better, smoother graphics accessible to more people without requiring them to spend a fortune on hardware. We had to think like Linux.

That’s where the best hack came into play: the “Fast Inverse Square Root,” which calculates the inverse of a square root in a clever way. It doesn’t actually perform the full calculations to get the exact value but uses a trick that works very well and gets an approximate value. Later, it uses a formula by Newton to verify if this approximation is accurate.

What it does and why

The Fast Inverse Square Root calculates ( f(x) = 1 / √(x) ) much faster.

It was first publicly noticed for its use in Quake III, primarily to compute the reflections of light—crucial for video games, especially shooters where guns emit additional light. Nevertheless, even in non-shooter games, a 3D world without light isn’t feasible because clear visibility is impossible in a dark room, mirroring reality.

When dealing with light reflection, especially in computer graphics, it’s often necessary to normalize vectors. Vectors are the triangles we referred to before. Normalization is scaling the vector to a smaller size while keeping it’s direction.

The formula to normalize, can be simplified to :

normalized(v) = v * (1 / ∥v∥)

And it’s the 1 / ∥v∥ part where the fast inverse square root comes to help, simply because

∥v∥ = √(n12+n22+…+nn2)

For example, the vector v=(3,4,0) can be normalized by :

--- Context :

v = (3,4,0),

normalized(v) = v * ( 1 / ∥v∥)

--- Calculate ||v|| to simplify the normalization term :

normalized(v) = v * ( 1 / ∥v∥) =>

normalized(v) = v * ( 1 / sqrt( (3^2) + (4^2) + (0^2) ) ) =>

normalized(v) = v * ( 1 / sqrt(25) )

--- Substitute ( 1 / sqrt(25) ) with fast_inverse_square_root(25):

normalized(v) = v * fast_inverse_square_root(25)

--- Evaluate fast_inverse_square_root(25) which returns 0.2 :

normalized(v) = v * 0.2

--- Simplify 0.2 which is the same as (1/5) :

normalized(v) = v * (1/5)

--- Replace v with its actual value (vector)

normalized(v) = (3,4,0) * (1/5)

--- ( vector * x ) => ( each value of the vector * x ), so :

normalized(v) = ( (3 * (1/5)), (4 * (1/5)), (0 * (1/5)) ) =>

normalized(v) = ( (3/5), 4/5, 0/5 )

Original Code

This is the original C code from Quake III, one of the earliest—if not the very first—pioneers of the Fast Inverse Square Root. The year was 1999…

float Q_rsqrt(float number)

{

long i;

float x2, y;

const float threehalfs = 1.5F;

x2 = number * 0.5F;

y = number;

i = * ( long * ) &y; // evil floating point bit level hacking

i = 0x5f3759df - ( i >> 1 ); // what the fuck?

y = * ( float * ) &i;

y = y * ( threehalfs - ( x2 * y * y ) ); // 1st iteration

// y = y * ( threehalfs - ( x2 * y * y ) ); // 2nd iteration

return y;

}

Breakdown of the Original Code

Here’s what happens on those lines: at the beginning, we define our function and its variables. You can ignore this part.

float Q_rsqrt(float number)

{

long i;

float x2, y;

const float threehalfs = 1.5F;

Then, we calculate some values we’ll need for Newton’s formula, which will be explained later. You can ignore this part for now.

x2 = number * 0.5F;

y = number;

Next, we define the size of the variable i. This variable plays a key role in the algorithm’s core line, which is the line following this one.

Look closely.

Even though “i” is a variable of type long, which is a type for simple numbers (1,2,3,4), is taking the exact value of “y”, which has the value of “number”, which is the given value we try to calculate for. However, even though “i” is long, it’s ending up with the bits of the variable “number”, which, is a float. We save the bits of a “float” to a “long” This is a preparation for the next line.

i = * ( long * ) &y;

This line, which we’ll call the “core line”, is the heart of our algorithm. We’ll break it down later to see how it calculates the inverse square root of a given number. This is the most important part.

i = 0x5f3759df - ( i >> 1 );

Next, we define the size of the variable y. This variable is used in the calculation for Newton’s formula. We assign the value of i (from the core line) to y and then perform the calculations. Newton’s formula essentially refines our initial calculation. We’ll explore Newton’s formula in more detail later.

You can ignore this part for now.

y = * ( float * ) &i;

y = y * ( threehalfs - ( x2 * y * y ) ); // 1st iteration

// y = y * ( threehalfs - ( x2 * y * y ) ); // 2nd iteration

At the end, we are just returning the value y, which is the value i we found from the core line, calibrated and validated through Newton’s formula. Ignore.

return y;

}

Breakdown of the “Core Line”

This is the “core line” as we saw on the original code :

i = 0x5f3759df - ( i >> 1 );

0x5f3759dfis just a magic number.

It’s literally a magic number hard-coded there, that just does the trick.

It’s in hexadecimal numbering system format.

In binary is0101111100110111010110011101111( i >> 1 )is binary shift to the left by one.

Look closely at this example:

If we perform a binary shift to the right by one on the value01000000100000000000000000000000, we end up with00100000010000000000000000000000.

As you can see, all the bits move one position to the right. We add a 0 at the beginning (leftmost position) to maintain the same size during the shift. The least significant bit (rightmost position), which was also 0, is discarded to keep the overall length unchanged. In this specific case, discarding the last 0 took place but it’s not noticeable because it was just another zero.

“Core Line” by hand, example

Let’s see an example of how we could do these operations by hand, using just an online binary calculator to make our lives easier.

We are going to calculate the fast inverse square root for 4, so we actually try to calculate 1 / sqrt(4).

- Our i, is going to be the number 4, and in binary normally 4 is just

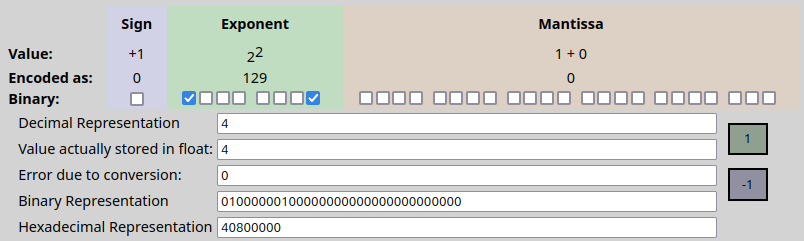

100BUT, be careful, as in the fast inverse square root algorithm, the i contains the bits of a float. So we need to convert 4 to float, which is much different and it’s0101111100110111010110011101111in binary. The use of a floating point calculator (like this) is strongly suggested. We talk about types later. - The magic number we encountered earlier,

0x5f3759dfin hexadecimal notation, translates to01011111001101110101100111011111in binary. It’s the same value represented in a different numerical system (binary instead of hexadecimal). Using binary will simplify the upcoming example. - Our formula is :

rsqrt = magic – (x>>1)and it’s based on the core line.

| rsqrt = magic – (i>>1) | Our formula |

| rsqrt = magic – (01000000100000000000000000000000>>1) | i is 4, float in type. If we use a floating point calculator to binary, 4 as a float in binary is 01000000100000000000000000000000. |

| rsqrt = magic – 00100000010000000000000000000000 | (i>>1) symbolizes binary shift to the right by 1. We apply it. 01000000100000000000000000000000 becomes 00100000010000000000000000000000 |

| rsqrt = 01011111001101110101100111011111 – 00100000010000000000000000000000 | We simply replaced magic with it’s value. |

| rsqrt = 00111110111101110101100111011111 | We simply did the binary subtraction using an online binary calculator. |

The result, is that for x = 4, the inverse square root, is 00111110111101110101100111011111 in binary, or 0.48310754 in decimal, if we simply use a binary to decimal online converter.

And actually, 1 / sqrt(4) = 0.5, which is very close to 0.483.

Types

It’s very important to note that fast inverse square root algorithm is tricking around the floating-point arithmetic, which is the arithmetic system where such trick is working.

If you try to convert those numbers in decimals or not follow the types exactly as they are, it’s not going to work.

So if you are doing it programmatically, you need to be careful to the fact that i must be a value of type long but it has to contain a the bits of a float number !

It need’s to be long in order for the binary shift to work properly, while it needs to contains the bits of a float because the trick is actually possible only in floating-point arithmetic.

In the code, we start with a float, “number”

float Q_rsqrt(float number)

We copy the value of the float “number” to the float “y”

y = number;

And then, this is the hackish part, we save the bits of the “y” float to “i” long.

This trick is called “type punning”.

i = * ( long * ) &y;

For example, the 4 looks like that in binary : 100. But the 4 looks like that as a float, in binary : 01000000100000000000000000000000. That’s because in a 32-bit float, the first bit is the sign (if the number is negative or positive), the next 8 bits are the exponent (power) and the next 28 bits are the mantissa (adjustment). Float is a special type to save decimals that does all this in order to save memory.

So, 01000000100000000000000000000000 means : “positive” “2^2” plus “zero” adjustment.

The types must be like that, because this is the recipe of fast inverse square root.

If you want to do calculations by hand, the use of a floating point calculator (like this) is strongly suggested.

Magic Number Origin

One of the most interesting aspects is that the origin of this magic number isn’t documented. We have to accept it for now, similar to π = 3.14.

| Hexadecimal | 0x5f3759df |

| Binary | 0101111100110111010110011101111 |

Newton’s formula

Those are the lines that Newton’s formula is being applied.

y = y * ( threehalfs - ( x2 * y * y ) ); // 1st iteration

// y = y * ( threehalfs - ( x2 * y * y ) ); // 2nd iteration

It’s used to calibrate and validate the value we calculated on “core line”.

Newton’s formula calculates the inverse square root of a number with much greater accuracy.

However, it requires an initial guess close to the true answer. Here’s where the algorithm shines: it calculates an approximation of the inverse square root, even if this initial guess has a large error. Then, with this ‘guess’ in hand, Newton’s formula takes over and refines the result to a much more accurate value.

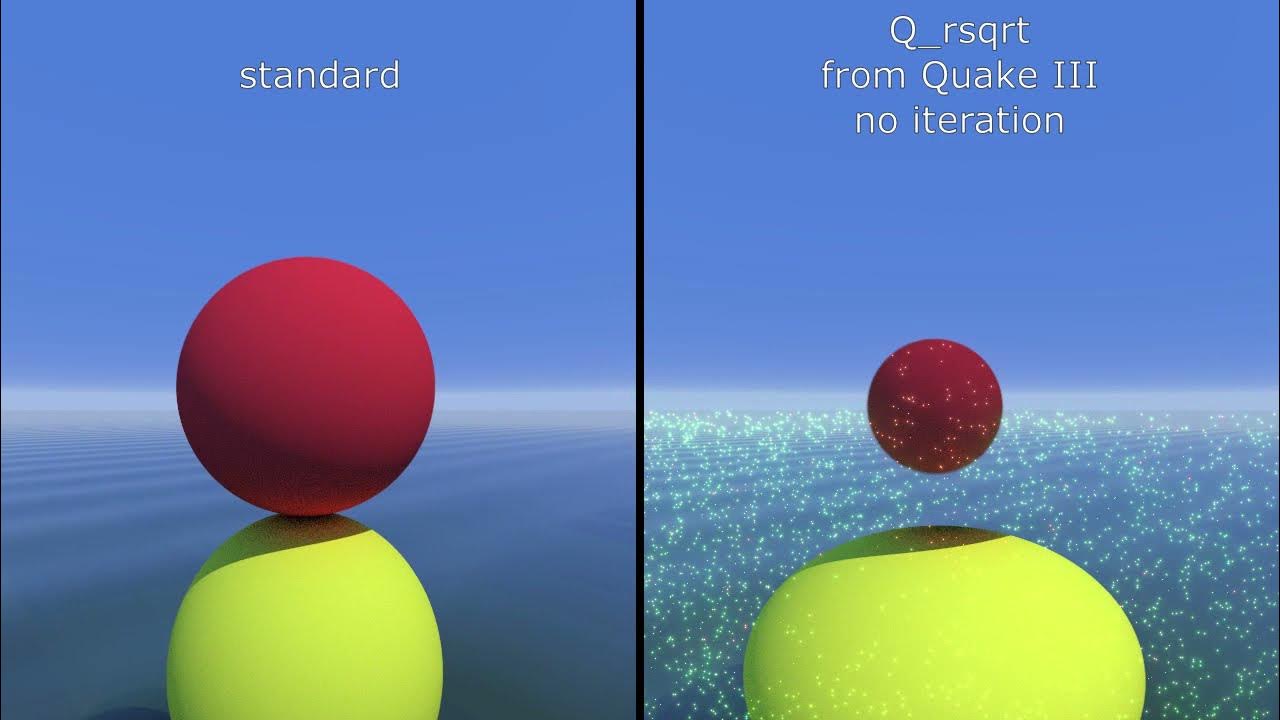

Without Newton’s formula, the fast inverse square root function would produce highly inaccurate results, leading to incorrect outcomes and distorted 3D worlds. For a clear visual demonstration, below is a video showcasing the fast inverse square root function used with and without Newton’s formula (including 1 and 2 iterations).

Conclusion

This piece of code helped propel Quake III to become one of the best-performing 3D games of its era. It essentially unlocked the potential of 3D graphics, transforming them from a distant dream to an everyday technology accessible to everyone, without the need for exorbitant costs.

While Quake III appears to be the software that popularized the use of this algorithm, it actually has a much richer history. The algorithm originated in a paper written by William Kahan and K.C. Ng at Berkeley University in May 1986.

The importance of this algorithm has led to its hardware implementation. Instead of being written in traditional C code by software engineers, it’s now embedded directly into the circuitry of many processors.

The fast inverse square root function is likely implemented in hardware on the device you’re holding right now. It’s probably integrated as part of one of the processor’s instruction sets on the list below :

| Platform | Device | Architecture / Platform | Instructions |

| Desktop and Servers, Mostly | CPU | x86 Intel’s SSE | RSQRTPS, RSQRTSS |

| Desktop and Servers, Mostly | CPU | x86 AMD’s AVX | VRSQRTPS, VRSQRTSS |

| Desktop and Servers, Mostly | GPU | NVIDIA’S CUDA | RSQRTF |

| Desktop and Servers, Mostly | GPU | AMD’s ROCm/HIP | RSQRT |

| Smartphones and Tablets, Mostly; Desktops and Servers (future) | CPU | ARM NEON | VRSQRTE.F32 |

| Smartphones and Tablets, Mostly; Desktops and Servers (future) | CPU | ARM SVE | FRSQRTE |

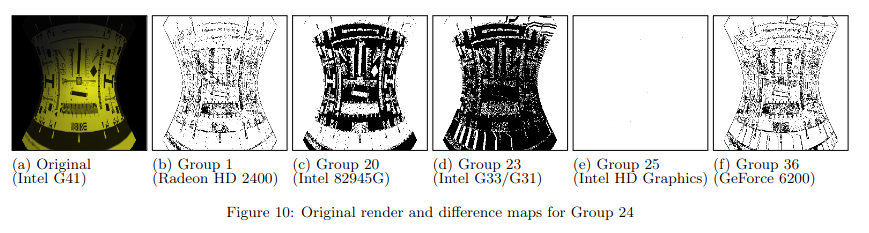

An unpublished report from CERN [1] reportedly showed that these instructions can produce slightly different results. While the variations are very small, it means that the same 3D world you see on one machine might differ slightly from the same world on another machine with different hardware, even though these minute differences are likely imperceptible to the naked eye.

( See footnote [1] for the paper. )

The 3D world you see on my machine could differ slightly from the one you see on yours, due to minute details in our hardware.

This has opened the door to a technique called “Canvas fingerprinting“[2] for potentially identifying users from the same machine even if they use different login credentials. Websites can render an invisible animation, calculate a unique identifier (hash) based on the rendering process, and compare these hashes across visits. If the hashes match, it suggests a high likelihood that the same machine is involved.

This technique was first recorded in the paper “Pixel Perfect: Fingerprinting Canvas in HTML5” [3] by Keaton Mowery and Hovav Shacham, researchers at the University of California, San Diego.

( See footnote [3] for the paper. )

Of course, the fast inverse square root instruction isn’t the only one that can cause variations in rendering; it’s just one example. Here’s the rendering from my machine on. It shows a uniqueness score of 2.83%, which is quite high. You can check your web fingerprint too on amiunique.org [4].

Footnotes :

[1] “A Study of the RSQRT and RCP Instructions on Intel and AMD Platforms”, J.M. Arnold, 20 Feb 2016 :

[2] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Canvas_fingerprinting

[3] “Pixel Perfect: Fingerprinting Canvas in HTML5”, Keaton Mowery and Hovav Shacham, University of California, May 2012

Comments

Great article! It explains the Fast Inverse Square Root algorithm so well. Loved the breakdown of the code and the history behind it. Really interesting to see how this little trick revolutionized 3D graphics 👏

Thank you ! I really appreciate your lovely comment ! 😉❤️